Will bioplastics be a big part of the industry's future, or its entire future?

Will bioplastics be a big part of the industry's future, or its entire future?

We've seen strong reaction from many Plastics News readers to the White House's ambitious bioplastics plan.

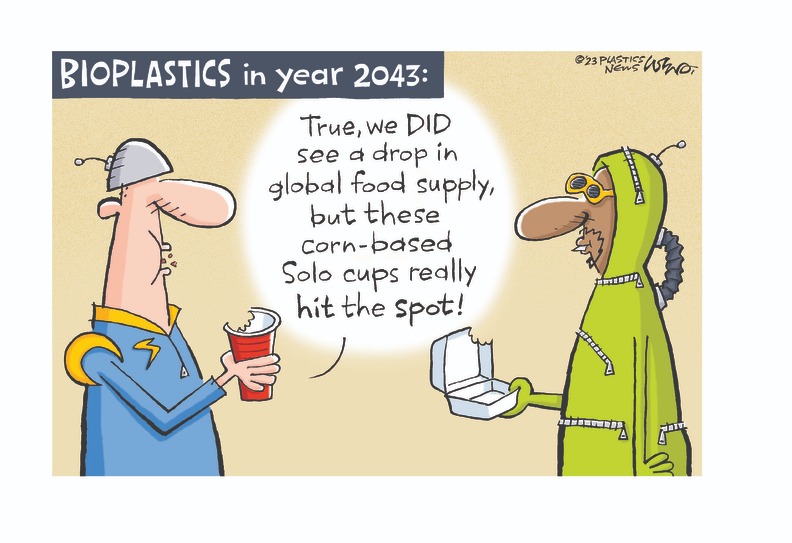

On March 22, President Joe Biden's administration announced what it called bold goals and priorities to advance American biotechnology and biomanufacturing. Prominent in the document is a call for a strategy to replace 90 percent of traditional plastics with bio-based materials in 20 years.

One industry expert we quoted called the goal "pure fantasy." On social media, I've seen it called a "pipe dream." I suspect that the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy would agree that skepticism is 100 percent an appropriate response.

Given the sharp political divide in the United States, I expected an even stronger response to this policy. Environmental issues are often polarizing these days — just ask manufacturers of gas stoves.

But we're not talking Green New Deal here. As environmental goals go, switching from conventional plastics to bioplastics is tame. There are plenty of environmentalists who would rather see 90 percent of plastics phased out completely. So look at the bright side: This is a political acknowledgment that plastics are going to be an essential part of the economy in 2043 and beyond.

We've been talking with a lot of industry experts, and I think Esteban Sagel of Chemical & Polymer Market Consultants in Houston summed up best how I feel about this: "It's clear that the polymer industry as it has existed until today needs to change. … To ensure that humanity can continue to benefit from the many benefits that plastics bring to our daily lives, we will need to do things differently."

Plastics are usually associated with the oil and natural gas sector, but that's only because those have been the most plentiful and least expensive feedstocks for polymers. That's going to remain the case for decades. But not forever.

Preparing for the day when fossil fuel feedstocks are too scarce or too expensive to make most plastics is both ambitious and enlightened. But it will require investment in technology and capacity, and incentives for companies to use sustainable materials.

But high density polyethylene and PET are currently the most commonly recycled conventional plastics, and there's already been a lot of work on commercializing bioversions of both resins.

Recycling is all about the ability to collect large volumes of clean, chemically similar materials. If major drink companies converted all of their containers to PLA or PHA — or PEF, which is PET's bioplastic cousin — recyclers could deal with that, too.

I assume that any government action to encourage (or force) a conversion from conventional to bioplastics will start with single-use plastics. That's where change can happen fastest and have the most impact.

If this happens, then it won't be easy and it won't be cheap. Getting public and political support for a dramatic change in plastics feedstocks doesn't look like a high priority. But it is possible, with the right combination of government incentives for using bioplastics or penalties for using fossil-based plastics.

There is growing awareness of climate issues, especially among young people. Convincing them that plastics shouldn't all be banned, but instead can be a core part of a new low-carbon economy, would be a victory for the plastics industry.